Building Bridges

Redding, California. Prior to 2004, Redding would not have been on my radar as a destination location. But since seeing Santiago Calatrava’s Sundial Bridge published in the architectural journals, it has been on my design bucket list. As a resident of a small, rural town in Washington State, located along the banks of the Skagit River, I’ve been in many conversations with community members and groups who for many years have dreamed of creating a pedestrian bridge over our river. And, of course, knowing what an attraction the Sundial Bridge is for Redding, my desire would be to make it architecturally spectacular, drawing visitors from all over the world to our beautiful, historic downtown.

I attended architecture school in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where the first Calatrava project I had ever seen was located. In 2001, the Milwaukee Museum of Art opened Calatrava’s much-acclaimed Quadracci Pavilion, including the entry bridge over Lake Drive, and the famous “brise soleil”, a sunshading device that moves through the course of the day to the sun’s angle. The project is stunning, and a major coup for Milwaukee to claim a small pin on the architectural map next to its big sister, Chicago.

It was no surprise to my wife that when planning our trip to France in 2008, the route had to include Bilboa, Spain, which was host not only to Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum, but a pedestrian bridge by Calatrava. The theme continued with a trip to Italy, where his bridge in Venice was a must on the itinerary. So, to have not seen one of his works that was closest in distance and relationship to our home, made it all that much more attractive, and somehow more difficult to reach.

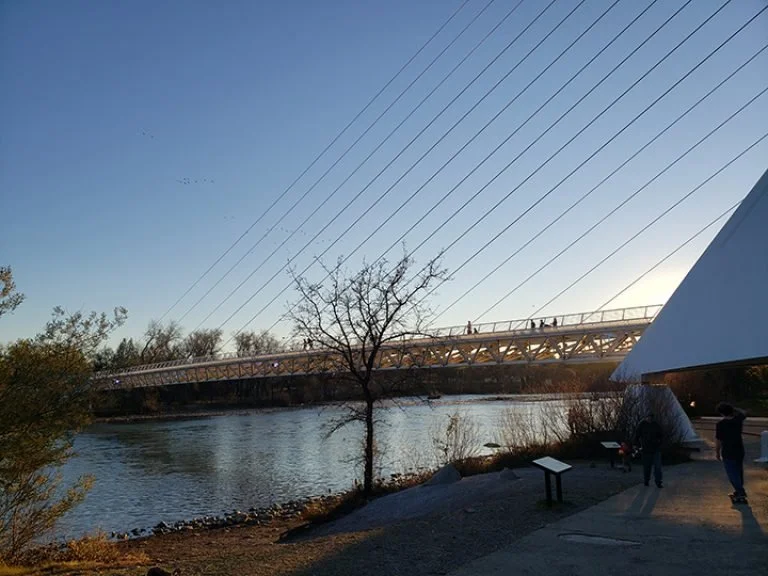

I got the opportunity to experience this incredible installation this year, on the way back from a road trip to California. We pulled up around 5:00 pm, as the sun was starting to set – which could not have been better timing to take in the sculptural beauty of the bridge’s forms against the sparkling river water and landscape beyond. I couldn’t stop taking pictures. Every couple of footsteps, there was a new view with a new pattern of light; a new sculptural form. The striking white concrete forms contrasting against the beautiful natural backdrop is visual eye candy to me. There’s no one vista or orthogonal, symmetrical composition here to frame. It’s a never-ending organic composition much like nature itself.

Calatrava has been criticized widely for his works having their issues, from leaking to having dangerous, slippery walking surfaces (for which lawsuits have ensued), and this is the ultimate struggle between creating public works of art and designing facilities required to be weathertight, durable, and protecting the public’s health, safety, and welfare. Calatrava is a structural engineer, and the engineering aspects of his firm’s work are incredible. The melding of the architect’s role in these projects is where the rubber hits the road, and often where the success or failure of a project resides. I’m conflicted on where to stand on this. On one hand, it’s easy to overlook some of these issues for the shear beauty of the object and experience. On the other, its our legal obligation and responsibility to design buildings and structures that do both – inspire and protect. Seeing these projects and how the people visiting them respond, inspires me to continue to strive to do both, to the best of my abilities.

Julie Blazek, AIA, LEED AP, CPHC®

Partner, HKP Architects